|

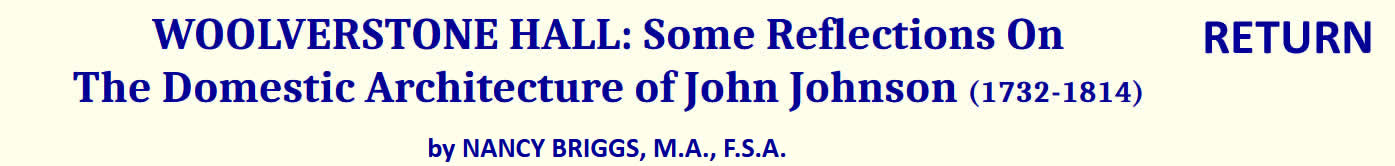

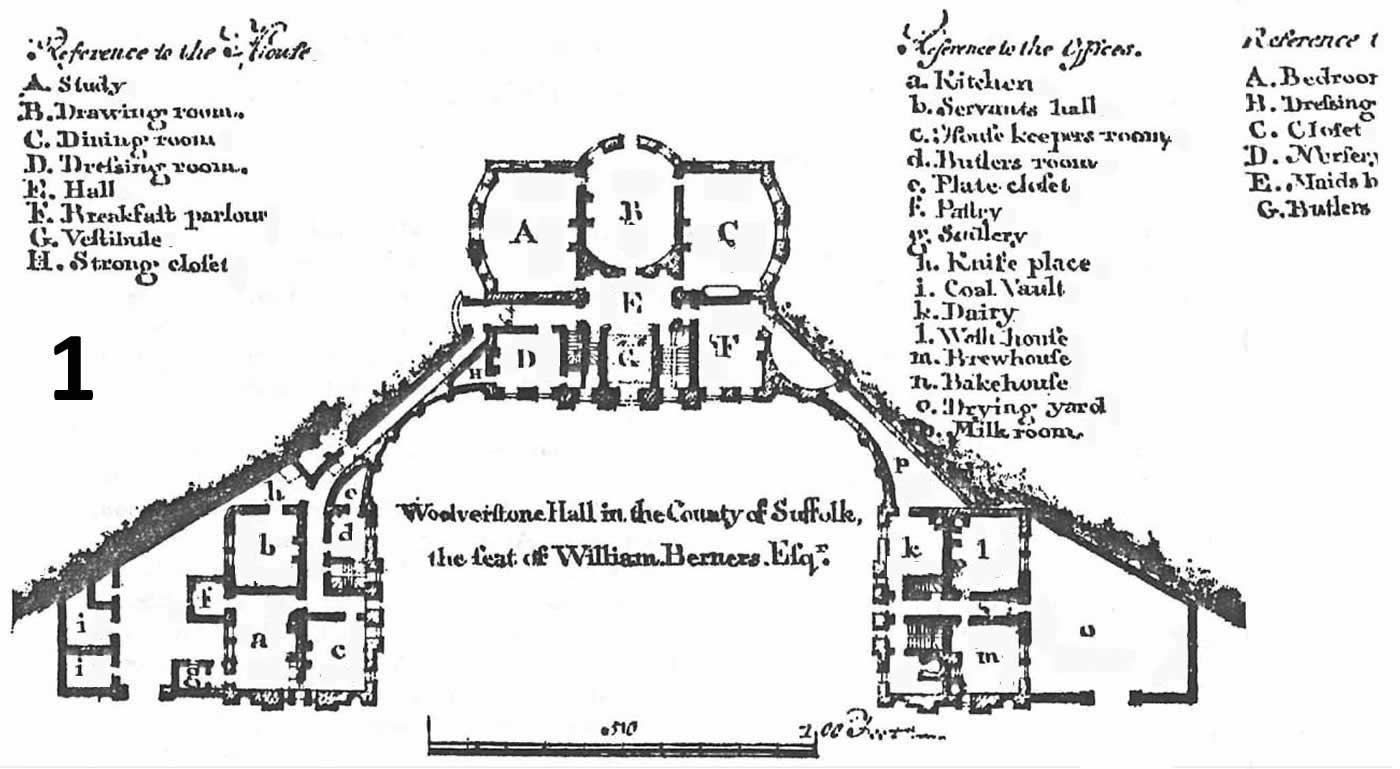

In 1777 JOHN JOHNSON of Berners Street, St Marylebone, exhibited at the Society of Artists a drawing of Woolverstone Hall, the seat of William Berners. The Woolverstone Hall estate had been originally leased by William Berners (1709- 1783) from Knox Ward (d. 1741). Berners purchased the estate out of Chancery for £14,000 c. 1773; the original house probably stood on the site of the present stables. Woolverstone Hall is said to have been erected in 1776, but the building is not documented, apart from the unsigned and undated plan now at Woolverstone Hall School (Figs. 1 & 2). Johnson's association with Berners provides the earliest definite information about the architect's career. He was born in Leicester on 22 April 1732, the son of John and Frances Johnson, and is possibly to be identified with the John Johnson, eldest son of John Johnson, joiner, who was admitted a freeman of Leicester on 22 April 1754. At the time of Johnson's death in 1814, it was stated in the Leicester journal that: "He left this town in early life possessing little more than strong natural abilities, which soon found their way in the Metropolis." By 1766 Johnson was involved in the development of the small Berners estate in St Marylebone; its frontage extended along Oxford Street from Wells Street to Rathbone Place, and as far north as the Middlesex Hospital. Development of the Berners estate had begun in 1738. The existing streets on the estate were laid out between 1750 and 1753 ; the first lease in Newman Street was dated 1750, with Charles (now Mortimer) Street following in 1759 and Berners Street in 1763. Leases of July and August 1766 from Berners to John Johnson of King's Street, Westminster, carpenter, relate to houses already erected by Johnson in Newman Street and recite articles of agreement dated 15 February 1766. Johnson also built houses in Berners Street, where he lived from 1767 to 1786, and Charles Street, where he held building leases from 1771. None of Johnson's houses on the Berners estate has survived, but 62-63 New Cavendish Street on the Portland estate dates from 1775 7 and has fine interiors. William Chambers was also closely associated with the development of Berners Street, but William Berners may well have been influenced by cost in preferring Johnson as the architect of Woolverstone Hall. Earlier, Johnson had been recommended to John Strutt of Terling Place as 'exceedingly honest, cheap and ingenious - what would you more?' Woolverstone Hall cannot claim to be Johnson's earliest country house; it was preceded by Terling Place, Essex (1771-3), Sadborow, Dorset (1773-5), and possibly by Killerton, Devon, and Clasmont, Glamorganshire. The design of Woolverstone Hall is more ambitious than most of Johnson's domestic exteriors; it consists of a pedimented 7-bay centre block of Woolpit brick, faced with Portland stone on the ground floor, and one-and-a-half-storey wings. The wings are shown on the plan (Fig. 1) drawn up for William Berners (d. 1783), but were almost certainly refaced and provided with attached Roman Doric porticoes by Thomas Hopper in 1823. The engraving in "Excursions in the County of Suffolk" appears to show Johnson's original design for the wings with a Venetian window on the ground floor. The outer niches in the wings shown in the early photograph may date from Johnson's time rather than Hopper's; the present ground-floor windows date from after 1937. Johnson's plan was completed by outer courts containing coal vaults in the left wing and a drying-yard on the right (Fig. 1). Hopper was probably responsible for the one-storey ranges with Roman Doric columns on the garden front, linking the house to the wings. The one-bay two-storey blocks, which are not shown on early photographs were added to the centre block early in the 20th century.

The garden front has a central bow window (B), a feature also used by Johnson at Sadborow, and later at Whatton House, Leicestershire, c. 1802. The plan shows that the study (A) and the dining-room (C) on the ground floor were also intended to have bow windows, but there is little evidence for their execution apart from a sketch plan in the Drake MSS. Hopper may have been responsible for the addition of the one-storeyed bay to the study (A). Johnson designed the quadrangular stable block south-east of the house; the entrance archway is faced in rusticated Portland stone with Coade stone keystone and paterae, and is surmounted by a Victorian water-tower. Johnson used the tripartite plan on a smaller scale at Langford Grove, near Maldon, Essex, c.1782, incorporating the stables in one of the two pedimented wings; the house was demolished c. 1953. Pitsford Hall in Northamptonshire, before 1785, originally also had a centre block and two wings, but has been much altered since World War II. Many of Johnson's designs are characterized by his use of Coade stone. The secret of manufacture of this artificial stone, often pinkish in tone when contrasted against Portland as at Woolverstone Hall, has not been fully elucidated, although the constituents are known from excavation of the Coade factory site at Lambeth in 1950. The Coade factory was established in1769. Its products can be identified from a series of plates published between 1777 and 1779,t he "Descriptive Catalogue of Coade's Artificial Stone Manufactory", 1784, and a handbook of 1799, Coade's gallery or exhibition in artificial stone. The handbook mentions Woolverstone amongst executed works in Suffolk. Johnson may have been using Coade stone as early as 1774. At Woolverstone Hall, the entrance front has Coade urns on the pediment with a central medallion of Diana.

The portico of attached Ionic columns has Coade capitals: the three centre windows are surmounted by pairs of Coade sphinxes flanking an urn. All the first-floor windows on both fronts have Coade balusters. Coade is also used for the eaves modillions and for consoles under the architraves of the centre window on the garden front, and of the outer windows on the first floor of the entrance front. At East Carlton Hall, Northamptonshire, one of Johnson's best-documented houses, rebuilt in 1870, 'the Artificial Stone Ornament in the Pediment' cost £12.12. Johnson's unexecuted design for Thorpe Hall, Thorpe-le-Soken, Essex, 1782, shows urns, a frieze of paterae and Corinthian capitals; the design may have been reused on the entrance front at Hatfield Place, Hatfield Peverel, Essex, 1791-5. The text of his published designs for the Shire Hall, Chelmsford (ALSO HERE: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-essex-65781433), states that 'the ornamental parts in the front are all finely executed in artificial stone'; details are given of the cornice, Ionic capitals and window consoles. Johnson's interiors frequently feature domes. The plan of Woolverstone Hall, with staircases on either side of the vestibule (G), placed the dome in the centre of the attic storey, in the position occupied by the hall (E) on the ground floor. At Woolverstone, the archways on the landing of the bedroom storey are similar to those on the staircase at Sadborow. The lower part of the Woolverstone dome has alternate oval and rectangular plaster panels; the latter with a Neo-classical urn between arabesques are similar to those in the library ceiling at Holcombe House (St. Mary's Abbey), Mill Hill. Above the panels at Woolverstone Hall is a bold acanthus frieze, of the type used by Johnson at New Cavendish Street, Langford Grove, and in the oval library at Bradwell Lodge, Bradwell-juxta-Mare, Essex, 1781-6. Between the frieze and the skylight at Woolverstone are garlands with drops, similar to those at Sadborow. The triglyph frieze with paterae below the Sadborow dome is the same type as that used on the staircase head at Woolverstone. The bold colouring of the Woolverstone dome and panels is a restoration of the original scheme. The later dome at Langford Grove was more ambitious, with garlands with drops, and bold acanthus frieze; the architrave with urns and fluting surmounted scagliola columns. Johnson's staircase at Woolverstone Hall was neither imposing, as at Langford Grove, nor attractive, as at Hatfield Place, with its oval plan, or Holcombe House, with a similar geometric stair. Its chief interest lies in Johnson's use of honeysuckle scroll balusters ; other examples of the design, executed in wrought iron with the anthemion motif cast, probably in lead, can be found in New Cavendish Street, c. 1775-7, Holcombe House, 1778, Bradwell Lodge, 1781-6, Langford Grove, 1782, and Hatfield Place, 1791-5. The accounts for East Carlton Hall, 1779-80, give details of ironwork, including 26 'Scroll Honeysuckle Pannels for Staircase' and 5 curved panels, but Johnson's source of supply is not indicated. The treatment of the vestibule (G) and hall (E) at Woolverstone Hall was paralleled at Langford Grove, where the coved hall had similar circular medallions. The colour scheme in this part of Woolverstone is a restoration of the original. At Bradwell Lodge, both the entrance and staircase halls, linking the Tudor and Georgian parts of the house, are coved ; the entrance hall has small circular medallions, similar to those at Woolverstone Hall and Langford Grove. The staircase hall at Bradwell Lodge is domed and has larger oval medallions similar to those in the hall (E) at Woolverstone. Niches flanking the door to the drawing room (B) at Woolverstone originally contained statues, a feature not known to occur elsewhere in Johnson's domestic work. It is less easy to comment on other characteristics of Johnson's interiors at Woolverstone. The fireplace in the drawing room (B) is white marble with Siena inlay and can definitely be considered Johnson's work; similar later examples exist at Bradwell Lodge and Hatfield Place. Johnson also used Siena inlay at Killerton and for the fireplace at East Carlton Hall, which cost £56. The white marble fireplaces in the dining room (C) and the study (A) at Woolverstone maybe contemporary or could possibly be associated with Hopper's alterations; it has been suggested that they could be the work of J. C. F. Rossi (1762-1839). The painted 'Pompeian' fireplace in the dressing-room (B) on the first floor echoes the bow and arrow and quiver and torch motifs of the ceiling, which has been restored in the original colours. Johnson also used these motifs in the library ceiling at Holcombe House and in the drawing-room ceiling at Langford Grove. The ceilings in the drawing room (B) and dining-room (C) on the ground floor at Woolverstone were also designed by Johnson, although the use of gold in the latter is not original; in the dining-room the panels in the form of radiating petals round the central motif, possibly based on a soffit in the Temple of the Sun at Palmyra, are almost identical in treatment with those in the ceiling of the front room on the first floor at 63 New Cavendish Street. The ceiling in the study (A) at Woolverstone may be associated with Hopper's alterations, but could well be as late as c. 1860. The treatment of the niche in the dining-room (C) is reminiscent of that at 63 New Cavendish Street. The present blue and white treatment of the walls in the dining-room (C) represents an old, but not necessarily original, colour scheme. The Woolverstone estate remained in the Berners family until it was sold by Geoffrey Hugh Berners in 1937 to Oxford University. The London County Council leased the mansion with 53 acres of grounds in 1946 and established the residential section of the London Nautical School there in September 1947. The school was reorganised as a secondary boarding-school giving a general education in September 1951. New buildings in the grounds, started in 1956, were opened on 18 May 1959. Woolverstone Hall belongs to the decade in which Johnson's practice as a designer of country houses developed and his work was exhibited in London. Johnson was appointed County Surveyor of Essex in January 1782 ; four country houses, including Benhall Lodge in Suffolk, which was rebuilt c. 1810, belong to the period 1781-1785. Only four major houses, including Hatfield Place, can be securely dated to the period 1791-1802. Johnson's health may have begun to fail when he was about 75; certainly no domestic work is traceable after 1808, although he did not retire as County Surveyor until the autumn of 1812. His public career is well documented and must be viewed as a major contribution to 'the work of a forgotten class of public servants - the County Surveyors of the 18th century'. Less documentary evidence is available for Johnson's country houses; this article has been chiefly based on stylistic analysis. In all his major commissions, he made full use of the Neo-classical ornament introduced by Robert Adam. If somewhat lacking in originality, the quality of Johnson's domestic work at Woolverstone Hall, and elsewhere, demands respect, however, and it would not be entirely fair to say that 'on the whole he was at his best as a civic architect'. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

B) Acknowledgement is also made of assistance and information received from:

|