| Coade Stone - From Wikipedia (LOTS more information HERE) |

Woolverstone Hall comprises a central block with flanking wings connected by colonnades. The central block is of three storeys: a rusticated basement, first floor and attic, and has at its front centre a pediment supported by four Ionic columns. The house is built of Woolpit brick, with Coade stone ornamentation, an example of which is shown below.

Eleanor Coade (3 June 1733 – 18 November 1821) was a British businesswoman known for manufacturing Neoclassical statues, architectural decorations and garden ornaments made of Lithodipyra or Coade stone for over 50 years from 1769 until her death. She should not be confused or conflated with her mother, also named Eleanor.

Lithodipyra ("stone fired twice") was a high-quality, durable moulded weather-resistant, ceramic stoneware; statues and decorative features from this still look almost new today. Coade did not invent 'artificial stone', as various inferior quality precursors had been both patented and manufactured over the previous forty years, but she probably perfected both the clay recipe and the firing process.

She combined high-quality manufacturing and artistic taste, together with entrepreneurial, business and marketing skills, to create the overwhelmingly successful stone products of her age. She produced stoneware for St George's Chapel, Windsor; The Royal Pavilion, Brighton; Carlton House, London and the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. Shortly after her death, her company produced a large quantity of stoneware used in the refurbishment of Buckingham Palace.

Born in Exeter to two families of wool merchants and weavers, she ran her business, "Coade's Artificial Stone Manufactory", "Coade and Sealy" and latterly "Coade" (by appointment to George III and the Prince Regent), for fifty years in Lambeth, London. A devout Baptist, she died unmarried in Camberwell.

In 1784 an uncle, Samuel Coade, gave her Belmont House, a holiday villa in Lyme Regis, her late father's town of origin. She decorated the house extensively with Coade stone.

Coade stone or Lithodipyra or Lithodipra (Ancient Greek: λίθος/δίς/πυρά, lit. 'stone fired twice') is stoneware that was often described as an artificial stone in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was used for moulding neoclassical statues, architectural decorations and garden ornaments of the highest quality that remain virtually weatherproof today.

Coade stone features were produced by appointment to George III and the Prince Regent for St George's Chapel, Windsor; The Royal Pavilion, Brighton; Carlton House, London; the Royal Naval College, Greenwich; and refurbishment of Buckingham Palace in the 1820s.

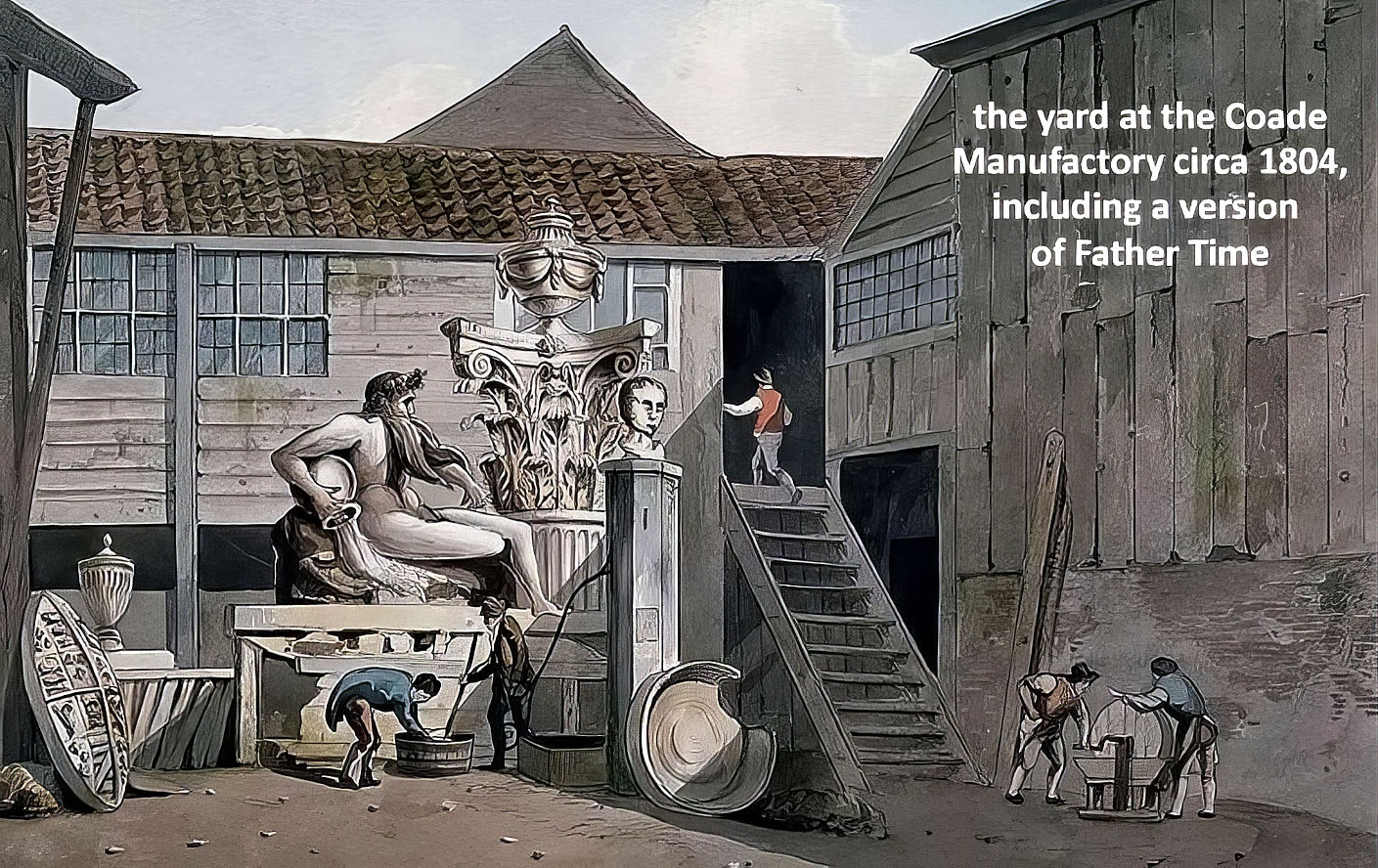

The product (originally known as Lithodipyra) was created around 1770 by Eleanor Coade, who ran Coade's Artificial Stone Manufactory, Coade and Sealy, and Coade in Lambeth, London, from 1769 until her death in 1821. It continued to be manufactured by her last business partner, William Croggon, until 1833.

History: In 1769, Mrs Coade bought Daniel Pincot's struggling artificial stone business at Kings Arms Stairs, Narrow Wall, Lambeth, a site now under the Royal Festival Hall. This business developed into Coade's Artificial Stone Manufactory with Coade in charge, such that within two years (1771) she fired Pincot for "representing himself as the chief proprietor".

Coade did not invent artificial stone. Various lesser quality ceramic precursors to Lithodipyra had been both patented and manufactured over the forty (or sixty) years prior to the introduction of her product. She was, however, probably responsible for perfecting both the clay recipe and the firing process. It is possible that Pincot's business was a continuation of that run nearby by Richard Holt, who had taken out two patents in 1722 for a kind of liquid metal or stone and another for making china without the use of clay, but there were many start-up artificial stone businesses in the early 18th century of which only Coade's succeeded.

The company did well and boasted an illustrious list of customers such as George III and members of the English nobility. In 1799, Coade appointed her cousin John Sealy (son of her mother's sister, Mary), already working as a modeller, as a partner in her business. The business then traded as Coade and Sealy until his death in 1813, when it reverted to Coade.

In 1799, she opened a show room, Coade's Gallery, on Pedlar's Acre at the Surrey end of Westminster Bridge Road, to display her products. In 1813, Coade took on William Croggan from Grampound in Cornwall, a sculptor and distant relative by marriage (second cousin once removed). He managed the factory until her death eight years later in 1821 whereupon he bought the factory from the executors for c. £4000. Croggan supplied a lot of Coade stone for Buckingham Palace; however, he went bankrupt in 1833 and died two years later. Trade declined, and production came to an end in the early 1840s.

Description: Coade stone is a type of stoneware. Mrs Coade's own name for her products was Lithodipyra, a name constructed from ancient Greek words meaning 'stone-twice-fire' (λίθος/δίς/πυρά), or 'twice-fired stone'. Its colours varied from light grey to light yellow (or even beige) and its surface is best described as having a matte finish.

The ease with which the product could be moulded into complex shapes made it ideal for large statues, sculptures and sculptural façades. One-off commissions were expensive to produce, as they had to carry the entire cost of creating a mould. Whenever possible moulds were kept for many years of repeated use.

Manufacture: Its manufacture required extremely careful control and skill in kiln-firing over a period of days, difficult to achieve with its era's fuels and technology. Coade's factory was the only really successful manufacturer.

The formula used was:

10% grog |

5–10% crushed flint |

5–10% fine quartz |

10% crushed soda lime glass |

60–70% ball clay from Dorset and Devon |

This mixture was also referred to as "fortified clay", which was kneaded before insertion into a 1,100 °C (2,000 °F) kiln for firing over four days – a production technique very similar to brick manufacture.

Depending on the size and fineness of detail in the work, a different size and proportion of Coade grog was used. In many pieces a combination of grogs was used, with fine grogged clay applied to the surface for detail, backed up by a more heavily grogged mixture for strength.

Durability: One of the more striking features of Coade stone is its high resistance to weathering, with the material often faring better than most types of natural stone in London's harsh environment. Prominent examples listed below have survived without apparent wear and tear for 150 years. There were, however, notable exceptions. A few works produced by Coade, mainly dating from the later period, have shown poor resistance to weathering due to a bad firing in the kiln where the material was not brought up to a sufficient temperature.

Demise: Coade stone was only superseded after Mrs Coade's death in 1821, by products using naturally exothermic Portland cement as a binder. It appears to have been largely phased out by the 1840s. There are interesting examples of its continued use for architectural embellishments as late as 1887.

READING: Coade Stone by Hans van Lemmen (only £3 on Amazon!)