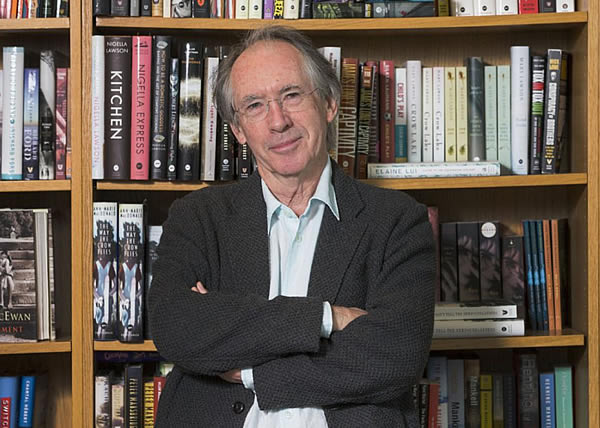

Ian Russell McEwan CBE FRSA FRSL (born 21 June 1948) is an English novelist and screenwriter. In 2008, The Times featured him on their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945" and The Daily Telegraph ranked him number 19 in their list of the "100 most powerful people in British culture". McEwan began his career writing sparse, Gothic short stories. The Cement Garden (1978) and The Comfort of Strangers (1981), his first two novels, earned him the nickname "Ian Macabre". These were followed by three novels of some success in the 1980s and early 1990s. His novel Enduring Love (1997) was adapted into an eponymous film. He won the Man Booker Prize with Amsterdam (1998). His following novel, Atonement (2001), garnered acclaim and was adapted into an Oscar-winning film starring Keira Knightley and James McAvoy. This was followed by Saturday (2005), On Chesil Beach (2007), Solar (2010), Sweet Tooth (2012), The Children Act (2014), and Nutshell (2016). In 2011, he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize. |

|

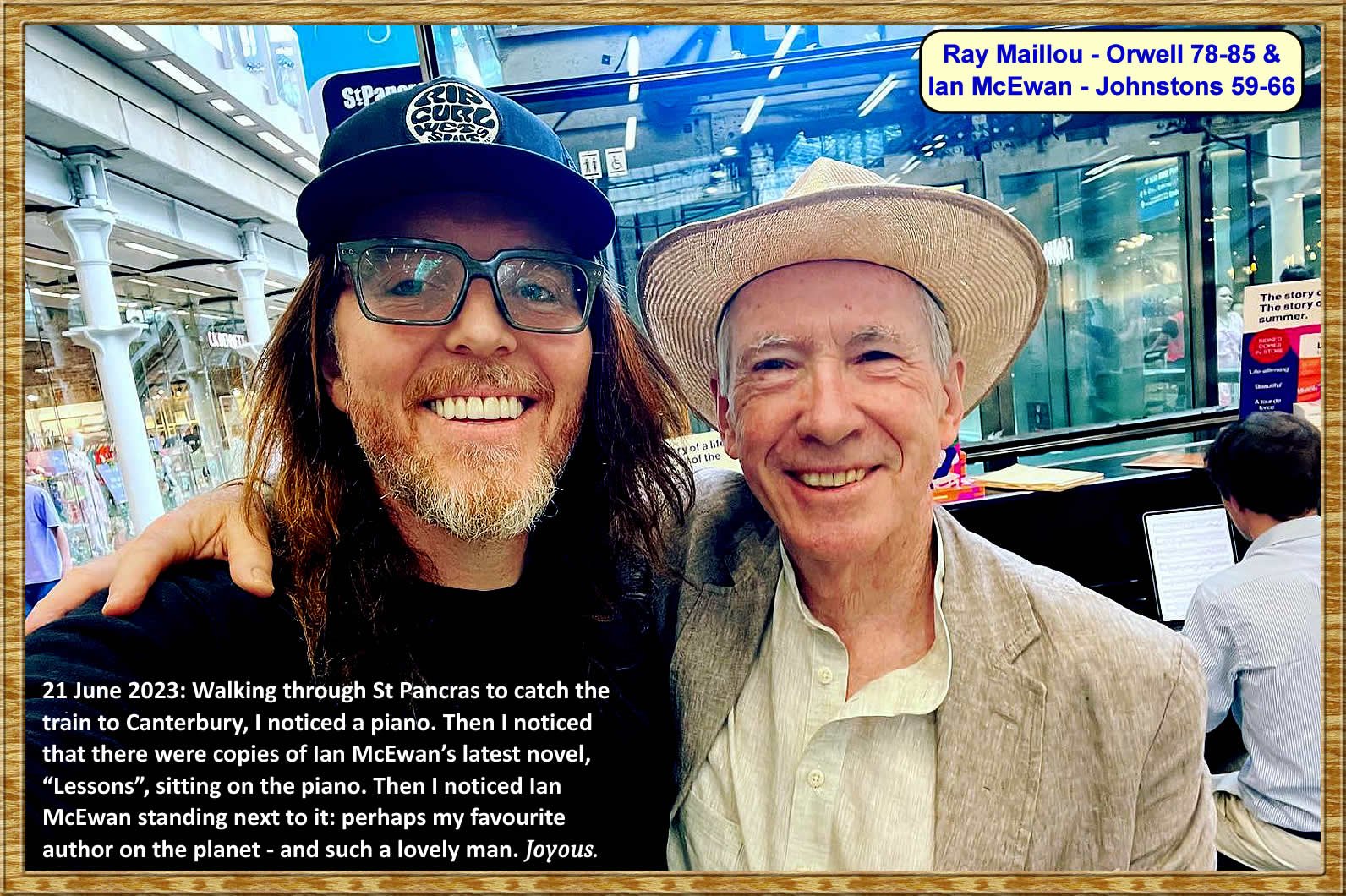

My Best Teacher (Amazon - https://www.amazon.com/My-Favourite-Teacher-teachers-difference/dp/190595929X) Pamela Coleman is talking to Ian McEwan As boarding schools went it was probably kinder and more civilised than most, but I was very disoriented. I was 2,000 miles from home and very shy. I found the lack of privacy devastating. It was noisy and the pastoral care was minimal. There was one matron between 60 boys. Her main concerns were the laundry and dabbing iodine on cuts. She wasn't in any way a mother figure. I sort of got through school. Until I got to the sixth form I'd been fairly mediocre. I had plenty of friends, but I hadn't shone in class, hadn't been trying particularly. Nobody encouraged me, nobody really knew I was there. Then, in the sixth form, I met Neil Clayton English teacher. It was a fortunate moment. I was suddenly hungry for the things he had to offer - excitement about poetry and literature. I realise now how young he must have been - I guess in his late twenties. He was cool, not in the hip sense, but he seemed a little impatient with school-mastering. He never wore a gown. He was quick-witted and enjoyed repartee. He had a streak of cynicism, even scepticism, about the world which was appealing to adolescents. There was a degree of hero worship. He was medium height and fairly handsome, played golf and cricket and had the ability, without a great deal of effort, to communicate a passion for reading widely. He had been educated at Cambridge and brought us very much that priesthood sense of studying literature. We barely touched the A-level syllabus in the first four terms and prided ourselves on knowing our way round the canon. His classes were fun. His enthusiasms were first-generation romantic poets. One of the first things he took us through was T S Eliot's "The Waste Land". He wasn't afraid of difficulty and he knew we would be proud of undertaking something different. He got things out of me that no one else had. I was keen to have his good opinion. Neil Clayton encouraged me to go for a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge, but I did little work. All sorts of emotional things got in the way and I fluffed the exam. I took a year off, did some travelling around Greece, worked as a dustman for Camden council and then went to Sussex university, where I read English. I began writing while I was there. Then I went to East Anglia to do an MA. I never had any lectures from Malcolm Bradbury, but I used to meet him in the pub and he and Angus Wilson encouraged me to write. I sent Neil Clayton a copy of my first book and others I wrote in the early years. He was always enthusiastic. After I left school our contact was only occasional. It is always a matter of luck who walks into your life at a certain point, and only as I get older do I realise how lucky I was to have had such a gifted teacher with such passion for literature and the ability to communicate. He now deals in antiquarian drawings and paintings. He once gave me a marvellous, leather-bound book, published in 1803, containing the first mention in print of William Blake. It is something I really treasure.

|

|