|

|

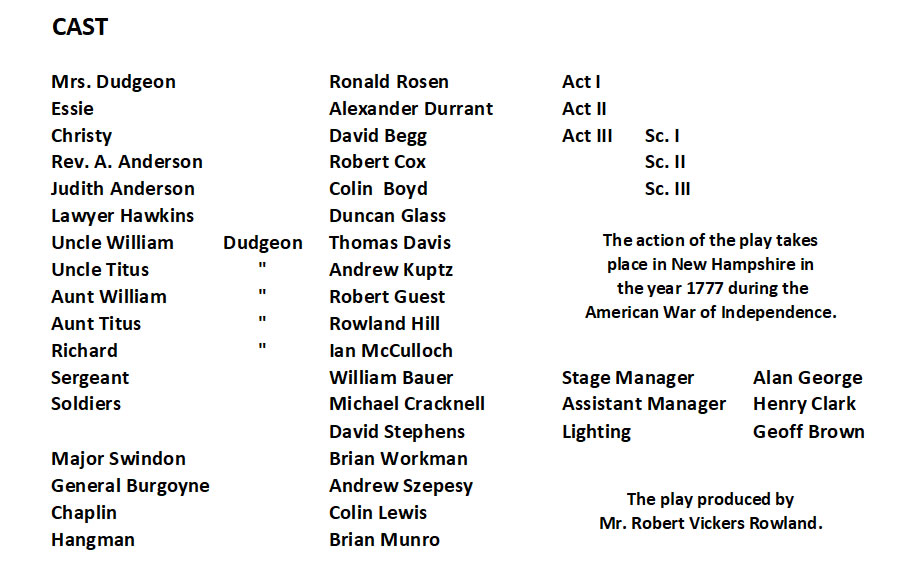

"THE DEVIL'S DISCIPLE" ("Janus" Spring 1956) OVER THE PAST few years the School Dramatic Society has built up for itself a fine reputation, and its latest production, "The Devil's Disciple," by G. B. Shaw, maintained the high standard. The production has been subject to many difficulties, because of its clash with the major musical work also put on this Spring, and it is a great credit to the producer (Mr. Rowland) and his cast that such a polished effect was obtained in so short a time. As is now usual, two performances were given, one to the School and one to the parents, and the applause at the end of each performance showed how well the production was appreciated. "The Devil's Disciple" is a difficult play to stage effectively, but in most cases the cast tried most expertly to get into their parts. Because of his fine performances in the past, we now tend to expect a very high standard of acting from McCulloch, and in this respect we were not disappointed. McCulloch is a "natural" on the stage, and with the flicker of his eyebrows, the wave of his hand or the well-placed sigh he really lives his character. The debonair, devil-may-care attitude of the play's hero, Richard Dudgeon, is particularly suitable to McCulloch's style of acting (compare his last part as Ivan Alexandrovitch Hlestakov in the "Government Inspector") and his performance was a pleasure to watch. In Rosen I think we have an actor of no small merit, and although he is new to acting (he had a small part in the "Government Inspector") his performance as the bitter - tempered, puritanical mother (a second Mrs. Clennam) was first-rate, and one could readily appreciate why Dick Dudgeon turned to Diabolism to escape her tyranny. Cox performed admirably as the Presbyterian minister-turned-militia-leader. and I thought the best scene in the play was when he was frantically struggling into his riding boots before fleeing the town to escape being captured by the English soldiers. Begg, who played the stupid Christy Dudgeon, deserves praise, for it is not a particularly easy task to act and look the fool unless one is type-cast. The weakest part of the play was undoubtedly that of Judith Anderson, the minister's wife, and it is all the more unfortunate since she is one of the key characters of the play. The part is very difficult to play, and it is made all the more difficult when a boy has to try and identify himself with this pretty, sentimental character. Unfortunately Boyd never looked like convincing us, and his part, which to be successful must be played with great sincerity and feeling, fell flat and wooden. He was expressionless and lifeless and passed even more into the background because of the fine acting of his fellow actors. The smaller parts were played with conviction. I quite liked Durrant as the scruffy-looking Essie, and we received two fine studies in English soldiering from Szepesy as General Burgoyne and Workman as Major Swindon. Those responsible for the sets and special effects for the play deserve nothing but praise. The lighting was cleverly used, and the five scene changes were excellent. The first scene in the dingy interior of the Dudgeon home was very well done, and the use of the shutter to let in the morning light was extremely effective. Likewise the cell scene was very realistically portrayed. The main thing that struck me about this production was its tone and atmosphere, and possibly in this respect it may be criticised. The play is set during the War of Independence, when passions were roused on both sides to shooting point, but this sense of revolution between the American fighting for the Rights of Man and the Englishman defending British Dominion was never achieved. One got the feeling that both sides were a slap-happy bunch who could get on quite well on their own and did not want any help from outside, thank you. Uncle Titus (Kuptz), the "upright horsedealer," looked as if butter would not melt in his mouth and if Christy and Uncle William were of the same calibre as the Springtown militia, General Burgoyne need not have worried at all, however suspicious he was of the English soldiers' marksmanship. The atmosphere was of a very jolly and happy bunch, and for better or worse the whole point of the play lost its significance. It is quite probable that it was better for the audience that the emphasis of the play was changed, for although the play had become more of a comedy, I still overheard one boy grumble: "Not so many jokes as last time, was there?" R. CROUCHER (VI) |

|

|