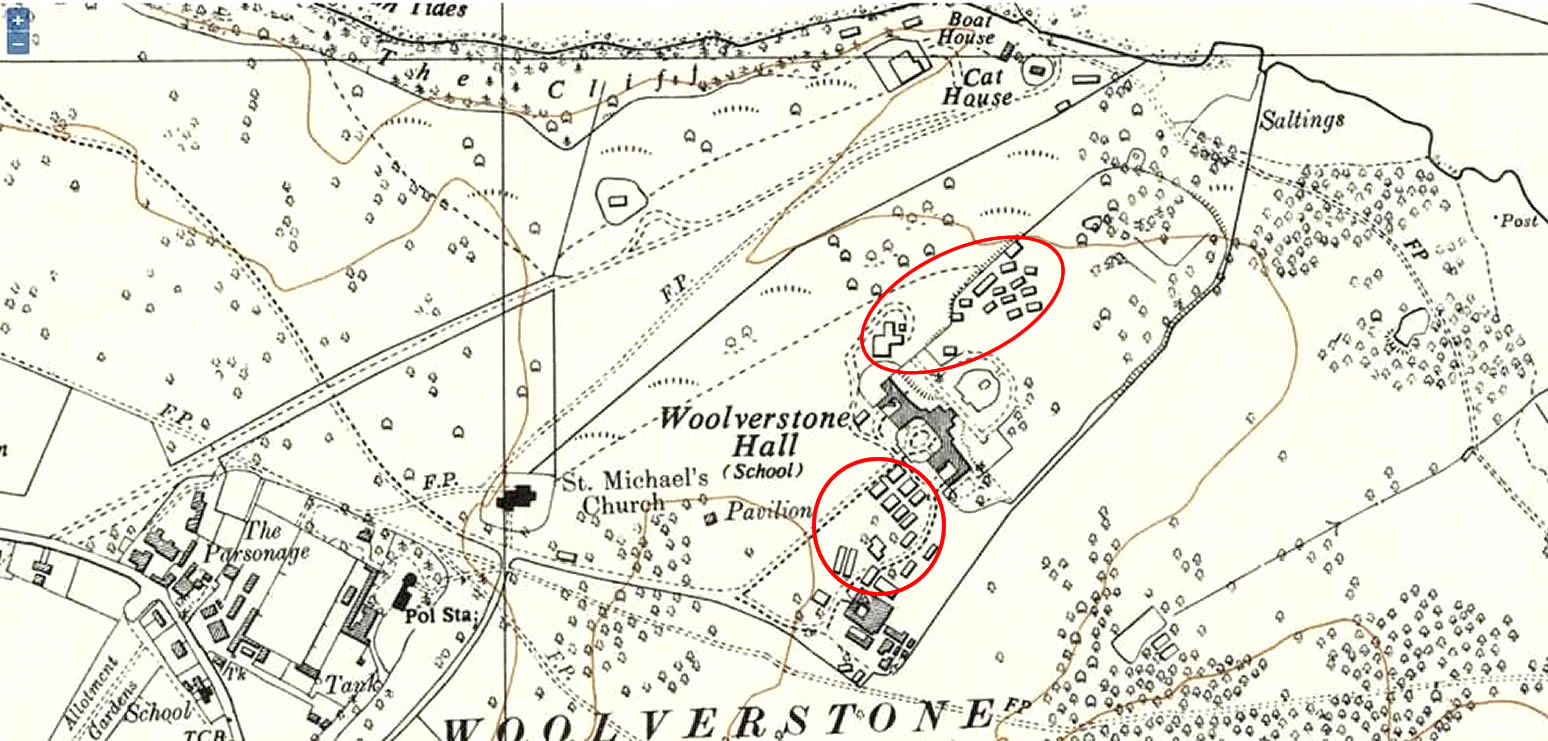

Nissen huts played a very significant role in the lives of WHS boys, especially in the first decade. I have always looked on them with a kind of affection, for all their minor inconveniences. In a way, they symbolized something that seems to have been rather lost in recent times: English ingenuity. There was an urgent need; there were limited resources - but WE FOUND A WAY TO DO IT. I find it analagous with the Battle of Britain; we were ill-prepared, but thanks to "the few" we collectively found a way, helped of course by Hitler's stupidity in thinking he could cower the populace into submission by bombing us when he should have stuck to bombing the airfields from which the few flew to defeat the Luftwaffe, or Napoleon thinking he could conquer the vastness of Russia ... and Putin! Another analogy is the pre-fabs which were ubiquitious in my youth: cheap and fast to construct: not Ritzy, but they did the job urgently needed at the time: it was the same with Major Nissen's great invention. Here is a map showing the prevalence of Nissen huts in the 50s, with the last at WH disappearing in 1992. (stolen from Wikipedia - full article here) Between 16 and 18 April 1916, Major Peter Norman Nissen of the 29th Company Royal Engineers of the British Army began to experiment with hut designs. Nissen, a mining engineer and inventor, constructed three prototype semi-cylindrical huts. The semi-cylindrical shape was derived from the drill-shed roof at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario (collapsed 1896). Nissen’s design was subject to intensive review by his fellow officers, Lieutenant Colonels Shelly, Sewell and McDonald, and General Clive Gerard Liddell, which helped Nissen develop the design. After the third prototype was completed, the design was formalized and the Nissen hut was put into production in August 1916. At least 100,000 were produced in the First World War. Nissen patented his invention in the UK in 1916 and patents were taken out later in the United States, Canada, South Africa and Australia. Nissen received royalties from the British government, not for huts made during the war, but only for their sale after the conflict. Nissen received some £13,000 and was awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order). Two factors influenced the design of the hut. First, the building had to be economical in its use of materials, especially considering wartime shortages of building material. Second, the building had to be portable. This was particularly important in view of the wartime shortages of shipping space. This led to a simple form that was prefabricated for ease of erection and removal. The Nissen hut could be packed in a standard Army wagon and erected by six men in four hours. The world record for erection was 1 hour 27 minutes. Although the prefabricated hut was conceived to meet wartime demand for accommodation, similar situations, such as construction camps, are places where prefabricated buildings are useful. The Nissen hut was adapted into a prefabricated two-storey house and marketed by Nissen-Petren Ltd. The standard Nissen hut was often recycled into housing. A similar approach was taken with the U.S. Quonset hut at the end of the war, with articles on how to adapt the buildings for domestic use appearing in Home Beautiful and Popular Mechanics. However, the adaptation of the semi-cylindrical hut to non-institutional uses was not popular. Neither the Nissen, nor the Quonset developed into popular housing, despite their low cost. One reason was the association with huts: a hut was not a house, with all the status a house implies. The second point was that rectangular furniture does not fit into a curved-wall house very well, and, thus, the actual usable space in a hut might be much less than supposed. Production of Nissen huts waned between the wars, but was revived in 1939. Nissen Buildings Ltd. waived its patent rights for wartime production during the Second World War (1939–45). Similar-shaped hut types were developed as well, notably the larger Romney hut in the UK and the Quonset hut in the United States. All types were mass-produced in the thousands. The Nissen hut was used for a wide range of functions; apart from accommodation, they functioned as churches and bomb stores among other uses. Accounts of life in the hut generally were not positive. Huts in the United Kingdom were frequently seen as cold and draughty, while those in the Middle East, Asia and the Pacific were seen as stuffy and humid. However, the adaptation of the semi-cylindrical hut to non-institutional uses was not popular. Neither the Nissen, nor the Quonset developed into popular housing, despite their low cost. One reason was the association with huts: a hut was not a house, with all the status a house implies. The second point was that rectangular furniture does not fit into a curved-wall house very well, and, thus, the actual usable space in a hut might be much less than supposed. In the UK, after the Second World War many were converted for agricultural or industrial purposes, and numerous examples have since been demolished. In Australia, after the war, Nissen huts were erected at many migrant camps around the country. |